The statement in pdf

The decision to stand in solidarity with the persecuted migrants…

When we began the #freethemoria35 campaign, after the events of July 18 (2017), in Moria’s detention centre, we knew that we would face many difficulties. We already had an idea of the difficulties we would encounter given the fact that we had no prior relationship with the persecuted migrants, the obstacle of different language, politics and culture, the financial burden of a trial, as well as the various people interested in the case who, each in their own way and for their own purposes, would involve themselves in the case. Most of the facts of the case were not initially known to us, and communication with the persecuted and development of the first solidarity actions were very difficult as 30 of the persecuted were immediately taken into custody to various prisons throughout Greece. What was crystal clear, however, was the brutality of the police operation, the random arrests that followed and the established feeling of fear for those trapped in Moria, which was further intensified a week later, when a sweep operation by the police took place inside the detention centre, with dozens of administrative arrests.

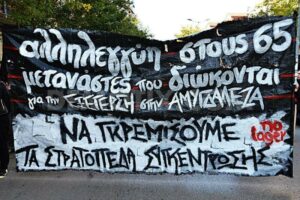

Uncertainty about the outcome of their asylum claims, fear of deportation, containment on the islands, miserable conditions in detention centers, violent daily confrontation with police forces and exclusion and marginalization by local societies, are the necessary mixture of pervasive powers and repressive instruments for the control of migrants. Any attempts to resist the marginalisation and dehumanisation experienced are met with violent mob and police attacks, followed by legal actions brought against migrants, proving the counter-insurgent role of the judicial authorities.

This was the case in the judical cases we have followed from the detention centres of Moria and Petrou Ralli (Athens), but also in cases where migrants attempted to publicly protest, such as the protest of Afghan migrants, whose decision to transfer their protest to Sappho Square led to a pogrom against them. The targeting of these migrants not only has a punitive effect for those who dare to resist, but also are intended to function as deterrent example for everyone else in the same circumstances.

The message is reenforced that migrants must remain invisible, and significant obstacles are placed to prevent the development of struggles against detention centres and against the modern totalitarianism within which these detention centres are being developed.

Despite the difficulties mentioned above, choosing to stand with them was the only option. After all, the main goal of the campaign, besides material and legal support that would be offered to the persecuted, was to bring the anti-migration policies of the Greek state and the EU back into the public dialogue and that of the movement. A similar case from the Petrou Ralli inferno and the decision comrades made to focus on that case in a similar campaign offered the opportunity to join these two struggles and have a broader impact. The emergence some time after of another court case against 10 migrants related to events that had taken place on July 10, which we didn’t know about earlier, but concerned people with whom we had developed relationships during the campaign, further expanded the campaign, but also added additional burdens.

Breaking through invisibility

Since the beginning, we had as our primary goal to combat the invisibility which threatened the case. The videos of police brutality that initially circulated provided some publicity, which drew the interest of various groups and organisations. Many rushed to express their discontent and to condemn, but it was easy to predict that once the mist of the teargas settled, and the persecuted had disappeared into the dungeons of the Greek state, the case would be resigned to the archives for most of these groups.

With the help of comrades from various cities in Greece and abroad, the publicity campaign began with various, mostly informative actions in order to carry out more powerful actions as we drew closer to the court date. Solidarity actions from Patra to Kavala, but also from Barcelona to Rojava, gave the case an important character, beyond the narrow borders of the Greek state in which it was taking place, and beyond the strictly mono-thematic character which is often afforded to the migrant struggles.

Conducting the trial

Faced with the mobilisation that took place in Lesvos and beyond, the state responded by sending the cases to be tried in the Joint Court of Chios Island. The move had a clear isolating effect as the obstacles to sustained solidarity in Chios alongside the persecuted are obvious. Choosing Chios also posed serious problems in conducting a fair trial. The defendants, who had been released from detention with restrictive orders in Mytilene (5 for the court of 35 and one for the court of 10), had no financial means to move to or stay in Chios. With this decision, they were excluded from their own trial. The same was true for witnesses in the defence of the two cases, since those who had not been deported or excluded because of the geographical limitations imposed on them because of the EU-Turkey deal would have to bear a considerable financial cost. Faced with this impasse, the various organizations representing the 5 for the first case and the solidarity assembly were called to cover these costs. The practice of excluding witnesses through various administrative measures, particularly in cases concerning migrants, is well established in the Greek judicial system. In dozens of cases in the past, we saw key witnesses, defenders or defendants, being expelled or excluded from attending court due to lack of legal documents. A political practice that essentially negates the access of thousands of migrants to justice, leaving them exposed to exploitation and fear.

A fair trial requires that the persecuted are given the opportunity to defend themselves regardless of their financial means. Ensuring this is a struggle against the classist nature of the judicial system.

The decision of the judicial system to deny a fair trial to the persecuted was made very clear at the Moria 35 trial through the (lack of) preparation for a trial where defendants speak foreign languages. The date of the trial was long known, as were the languages spoken by the defendants. However, when we arrived at the trial we saw that not only were the appropriate interpreters missing, but that the judges themselves were unconcerned about interpretation. The 35 accused became the audience in a foreign language play that was not dubbed or subtitled. This was a production, however, in which their future was determined. The same became clear during the the defence witnesses’ testimony and the testimony of the accused. The court not only interrupted the defence witnesses, not allowing them to testify to what they knew or to expand their testimony into the political nature of the trial, but was extremely threatening and aggressive with most witnesses. For example, the judge repeatedly threatened the first migrant witness who attempted to testify, while with another witness, a member of the solidarity assembly, the prosecutor did not hesitate to strongly attack him when he refused to testify to what she was suggesting to him. And if defence witnesses were not given sufficient time, there were no pretensions of giving sufficient time for the accused’s testimony. It was obvious that for the court there was absolutely no importance or procedural value to what some black migrants would testify when they had earlier heard the false testimony against them of so many cops. All the evidence presented showing the arbitrariness of the police’s raid, at a time and place where nothing was happening, was given no significance. The outcome of the trial seemed to have been decided from beforehand. That was also exactly the case in the trial of Petrou Ralli, where the audiovisual material proving the unjustified assault of the guards against incarcerated migrants, were not taken into consideration in the end.

The decision reached in the case of the Moria 35 could be misleading given its ambiguous nature. On the one hand, the accused were acquitted of the most serious charges, which allowed them to be released from state prison. On the other hand, for the lesser charges they were subject to penalties that not only justify the arrests, but also caused them further problems. Based on this conviction the persecuted were punished a second time for the offences for which they had just been released, as on returning to detention centers they were taken to the closed facilities as recognized troublemakers. Also defendants who had their asylum applications rejected during their time in detention were immediately placed on the list for deportation, something which has so far been prevented by the further mobilisation of the solidarity movement and lawyers. Faced with this treatment, so far, one of the 35 persecuted, who had already been trapped for months on the island, and for nine months in Greek prisons, withdrew his asylum claim and was deported to Turkey.

This exclusion is experienced by so many thousands of migrants who are forced into the judicial system without having the same basic rights that exist for native and Western citizens. The system fails them as they are permanently confronted with the Scylla and Charybdis of the criminal and administrative mechanisms of dehumanisation and repression.

Facing the arbitrariness of their arrest and trial, as expressed by the persecuted themselves to the comrades who were close to them, the only thing that made them feel safe was the presence of people in solidarity that ensured them that, no matter what happens, there would be someone to bear witnesses, and prevent them from getting lost in the jaws of the judicial system. Unfortunately, it is easy to imagine the fate of so many migrants dragged into the courts without the support of the movements or the visibility that the migrants had in these cases.

Aside from the distance we traveled to reach the trial and the court’s hostility, the climate of fear created in Chios in the face of the trail was also serious. In a city without any substantial prior experience in a central political trial, publications in local newspapers and blogs cultivated a highly aggressive image of the solidarity actions that had been organized, giving the police forces the excuse to set up an operations beyond any logic within and around the court. Especially during the early days, the accused and the people in solidarity, were found confronted by the entire Chios police force with multiple controls and constant surveillance. It should also be noted that there were elements of the local solidarity movement that had fallen in the same trap of fear and reproduced the same fear tactics. In the state’s desire to isolate the trial on the island of Chios, an unfortunate coincidence came to reinforce its isolation. A ferry strike by the workers union, which took place the last two days before the trial began, excluded the presence of comrades who were planning to travel from further away. But the feeling of isolation was broken by a considerable mobilization of comrades living in Chios, who both provided everything we needed in the unknown landscape of Chios, and were present throughout the two trials that took place.

The complex role of NGOs

Another important aspect we faced during the campaign was the role of NGOs. Much has been said regarding the role of these organizations in the management of migrant populations. Just as in the rest of the field, so in this case their dual role has emerged.

Following the events in July, several NGOs appeared willing to take part in the legal support of the 35 persecuted. As expected, as soon as the publicity of the case decreased in anticipation of the trial, many of them left the case without even informing the migrants they represented. In addition to that, the president of SYNYPARXIS, an NGO mainly consisting of SYRIZA members, who had also abandoned the two migrants who it had been representing just 1 month before the trial, appeared at the court with the intention of testifying as a defence witness in the trial. Facing the inconsistency and ridiculousness of such a proposition he was forbidden by the solidarity assembly. EURORELIEF’s role, compared to that of many NGOs, however, was particularly important in the case of 10 persecuted migrants for the events of 10 July. We remind you that during the events, the containers hosting the offices and warehouses of this organisation within the center of Moria had been targeted and burned due to organisation’s role within the center, always in full collaboration with the authorities. The head of the NGO, Jeremy Holloman, not only identified to the police a migrant he recognized during the riots, but he also collected audiovisual material from the employees’ and volunteer smartphones, which he handed over to the law enforcement authorities for further investigation. Through this material, criminal charges were brought against 4 additional people.

However, it should be noted that other NGOs involved in the case, independent to the reasons that each of them may have done so, have worked positively in defending migrants by offering them dignified legal representation. Some were assisting them not only throughout the course of the trial, but also in the preparation of their subsequent asylum applications after they were released.

Further Conclusions

Judicial arbitrariness against persecuted migrants cannot be seen separately from dozens of other cases of comrades and people that had been in resistance. Being themselves or even their relatives dragged in kangaroo trials. We are increasingly viewing cases where the judiciary performs a counterinsurgent role as a main component of state and capitalist power. Blind persecution, imprisonment and unsubstantiated convictions will continue to be used as tools against those who question the advance of modern totalitarianism over their lives or the lives of others.

What is extremely worrying, however, is the normalization of mass and blind judicial prosecutions. In Lesvos, the number of persecutions against migrants from the detention centre of Moria, supposedly for events they have caused, is impossible to know. Criminal prosecutions for cases of non-existent incidents, expulsions and deportations of those who assume more central roles in the organization of migrants, as well as persecution of those witnessing racist and criminal events against the imprisoned population are common.

In this situation, where more and more detention centers and populations are in a state of exclusion, it is imperative to stand with all our strength next to the persecuted. Despite the efforts of the authorities, the isolation imposed on them is broken, encouraging them to continue their resistances but also linking them with local movements in the direction of common struggles. In practice, it may seem impossible to follow all the judiciary cases. The judicial prosecution industry is built to overwhelm the time and material capabilities of the movements. But solidarity needs to be present in as many points as possible, building these bridges.

To allow solidarity to expand to more and more arenas ….