Lesbos island is still the main point of arrival of migrants from the Turkish coast. The number may be lower than the two previous years, however 3917 had arrived to Lesbos in 2017, up to August 2[1]. Contrary to the dominant racist rhetoric that speaks of «economic immigrants», more than 60% of them comes from the war torn regions in the Middle East and Afghanistan, 1/3 of which are children. During the last month it’s been observed that no other islands are used as points of arrival, like Chios and Kos, but that networks direct the vast majority of migrants to Lesbos.

This condition feeds more and more intensely into the contradictions in the local community. With a large part of the local economy, especially of the city of Mytilene, directly depending on the implementation of the anti-migration policies, and another part trying to point out this condition as the point of devaluation of other fields. This leads to a conflict of interest, with each side using all the influence they have to put political pressure. But since none of the two sides is contradictory with the essence of the anti-migration policies themselves, the question that remains is how will the latter continue to repeat themselves, with the least possible cost.

The situation in Moria detention centre

For some time a while back, local and imported police forces took up the task of deterring the migrants from being at the city centre, especially at night, and tried to achieve that through a process of intimidation. Intensified patrols with constant controls, arrests and beatings changed the image of the city centre dramatically. Migrants were forced to, for the most part, withdraw to Moria’s detention centre and the public camp of Kara Tepe, and visit town only for the most essential.

After the interventions that took place during the spring which increased the centre’s capacity, most of the tents were removed from Moria’s detention centre, and so the migrants were either transferred to other places or they were put into the new containers that were brought there. The migrants that are still kept in the detention centre are: a) new arrivals, b) people without any ‘vulnerability’ status, c) unaccompanied minors that haven’t been transferred to one of the houses for minors, and d) detainees in the pre-removal detention centre (PROKEKA), which is also located in the centre. According to their complaints, the detention conditions are stilll horrible. The live in a status of police brutality and arbitrarines, while there are continuous complaints about the meals they are given, as well as for the cleanliness of the centre, in which more than 3,000 persons are forced to live. Amongst them, as is also revealed through the latest reports by Human Rights Watch[2] and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)[3] who have access to this place, there are many unaccompanied minors and other vulnerable groups, with no protection whatsoever provided to them. Additionally, since May 2017, even in situations where they are granted ‘vulnerability’ status from registration, they are forced to remain on the island until their first interview, instead of being allowed to move to Athens like they were in the past.

Another area that has serious problems is the health service inside the detention centre. Since the end of May, when the contract between the Ministry of Health and Médecins du Monde (MDM) ended, until such time as the health service is taken up by the Centre for the Control and Prevention of Diseases (KEELPNO), the health support of the migrants in the detention centre is undertaken by the NGOs ERCI and Greek Red Cross, with little staff.

More than anything else, however, the biggest stress for the migrants is because of the extremely slow processing of their asylum applications, as well as the negative decisions that are issued en masse. To this should be added the impaired legal support that most of them have. After the end of contract between a well-known NGO and UNHCR, for the anticipated provisions, only a few legal councillors remain in the centre, so that the needs are met. The result of this is that most migrants are not sufficiently informed about their rights relative to the asylum application processes or, worse, relative to appealing against rejections, while they are also left exposed to the foreseen punitive processes of the legal framework.

The long-term wait, as many of them have been on the island for more than a year now, the uncertainty about what will follow, and the psychological, physical and financial exhaustion create a suffocating situation. The conditions in the detention centre are anything but safe for most of the migrants. The centre shows clear signs of ghettoisation, always with the weakest as victims.

Organisation and resistance of the migrants

In this situation, migrants have tried variously to organise and resist the conditions that have been imposed on them. The detention centre wings have been split mostly according to place of origin and spoken language, thus intensifying the feeling of micro-communities within them. Since the winter, so called ‘community leaders’ have been selected for almost every community, with the duty to act as mediators between their community members and the authorities.

The communities are never short of tensions, as the authorities’ choosing to prioritise the examination of the asylum applications of people from places that have a higher probability of being granted protection status, along with ethnic and racial differences that already existed, create antagonistic feelings among the migrants.

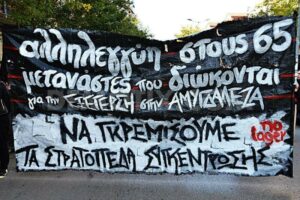

In this reality, against the backdrop of state coercion and repression, migrants put up resistance more than a few times. Most demonstrations target the asylum services and certain NGOs who play the role of the lackeys of the authorities. Blockading offices of services, damaging of equipment and small-scale riots are the most common forms of demonstration. The migrants mainly demand improvement of the living conditions in the detention centre, swift and quick processing of examining of the asylum applications, and a stop to the deportations and the returns to Turkey. To their demands, the authorities respond with more and more violence. The height of repression of this kind were the events between July 17 and 27. The police forces’ answer to the demonstrations of July 18 was even more violent and with random arrests, which resulted in the injuring of tens of migrants, and the arrest of 35 migrants who were sent to the court under heavy charges[4]. A few days later (27/07), police forces aided by extra personnel that arrived on the island from Athens and Thessaloniki, performed a “sweep operation” inside the detention centre, with intimidation, and arrests. All this resulted in many migrants being terrified and fleeing the detention centre, looking for accomodation in safer spots, while those who were forced to remain in the centre did so under the threat of similar treatment.

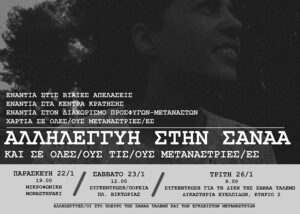

During this last month, another hunger strike is in progress. The people on the hunger strike that began on June 29 were brothers Harash and Amir Hampay, along with Hussein Kozhin and Bahrooz Arash. Amir Hampay, H. Kozhin and B. Arash were held in the pre-removal centre of Moria, as their asylum requests had been rejected for the second time too. Although they have appealed to the administrative court against these verdicts, the authorities have held them for many months. In fact, that had tried to deport Amir Hampay while the examination of his case was still ongoing. At the same time as the three strikers that are held in Moria, Harash Hampay is also on hunger strike since June 30 in Mytilene’s central square, to show solidarity and try to disrupt the veil of invisibility created by Moria’s isolation that shrouds the struggle of his comrades. However, his presence at a public spot has exposed him to constant harassing from the local authorities, as well as threats from local fascists. The first positive outcome was the decision to stop the arrest of Amir Hampay on 21/07. H. Kozhin and B. Arash stopped their strike on 01/08, as the strike’s health consequences were becoming increasingly dire, and under the reassurance and promises they got that the process to stop their arrest would start soon. However, Harash Hampay decided to continue the strike, until they are finally freed.[5]

Meanwhile, the last month and a half has seen the creation of a group consisting of migrants and people in solidarity that’s about the issues that are faced by LGBTQI+ migrants. The group was created because of the everyday threats, beatings and violations that LGBTQI+ folk are subjected to, both inside the detention centre, and in the city. In such wretched conditions as those that result from the anti-migration policies, patriarchal and sexist stereotypes become manifest in their most violent form. The group’s goals are the empowerment of its members and to demand that the danger of the situation they find themselves in because of the authorities to be acknowledged.

With more than 3,200 people dead in the Mediterranean so far in 2017, and many thousands trapped in various detention centres in European borders and mainland, it is obvious the all-out war against migrants is as intense as it had been, even if now you won’t see it on the TV screen. The Greek government has already announced the exacerbation of its attacks, through the building of new closed-type deportation centres on the islands, and violent repression of any kind of demonstrations of migrants and those in solidarity, as well as the later’s infrastructure.

Musaferat

08/08/2017

[1] https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5179

[2] http://www.independent.co.uk/News/world/europe/child-refugees-greek-camps-adults-abuse-suicide-greece-middle-east-north-africa-lesbos-moria-a7849586.html

[3] https://msf.gr/magazine/dramatiki-epideinosi-ton-synthikon-gia-toys-aitoyntes-asylo-sti-lesvo

[4] https://vimeo.com/226277179

[5] Since the publication of the present note, there have been good developments for the case of Hussein Kozhin and Bahrooz Arash. Both have been released on Tuesday 08th August. Harash Hampay stopped the hunger strike after this.

Previous information notes here

2 pings

[…] φτάσει στη Λέσβο μέσα στο 2017, μέχρι και τις 2 Αυγούστου[1]. Σε αντίθεση με την κυρίαρχη ρατσιστική ρητορική που […]

[…] Πληροφορίες για την υπόθεση εδώ και εδώ. […]